Poverty and Welfare in the First Republic: Unemployment and the Place of Origin Certificate

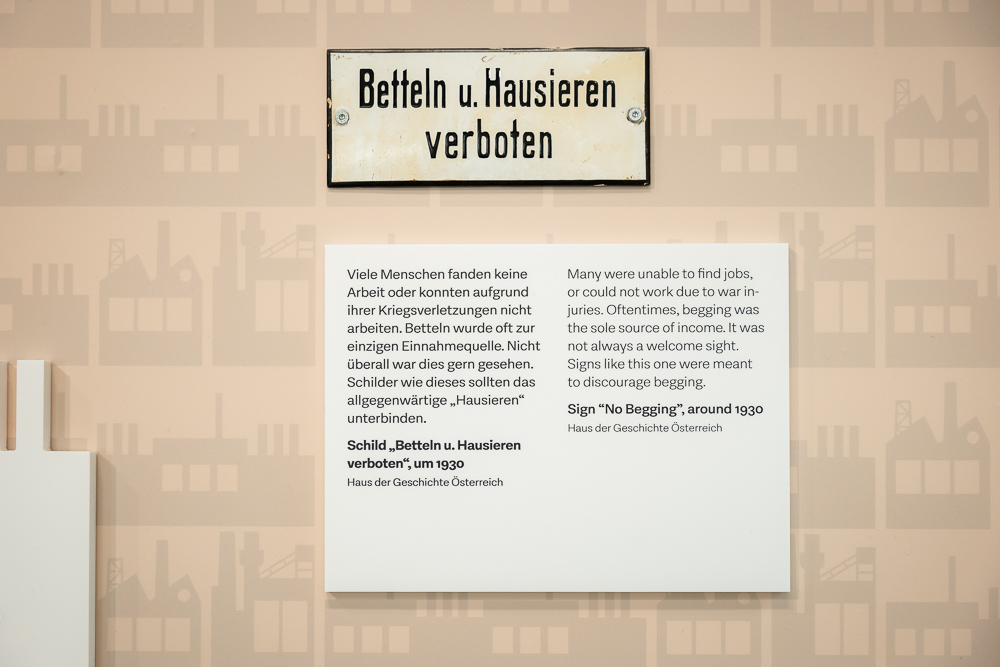

This sign that forbids begging raises the question of how a society deals with poverty and social inequality. This remains a key question today in debates concerning state social welfare benefits.

In the First Republic begging and vagrancy were forbidden in many areas. Signs like this one were intended to keep beggars away.

That was also the idea for the “Automatic begging machine” that you see here. This invention from the 1920s was never realized. You can pull a coin out of the reconstruction of this machine. The coin contains a link to the House of Austrian History’s Online Encyclopedia of Contemporary Austrian History with several articles on the topic of poverty.

Following the First World War, large parts of society were affected by poverty. Food and fuel for heating were scarce, and the Spanish Flu rapidly spread and claimed thousands of lives.

The young Republic was also left to deal with the economic consequences of the war, including the devaluation of its currency. The currency became stable in the 1920s with the introduction of the Schilling and with the help of international loans.

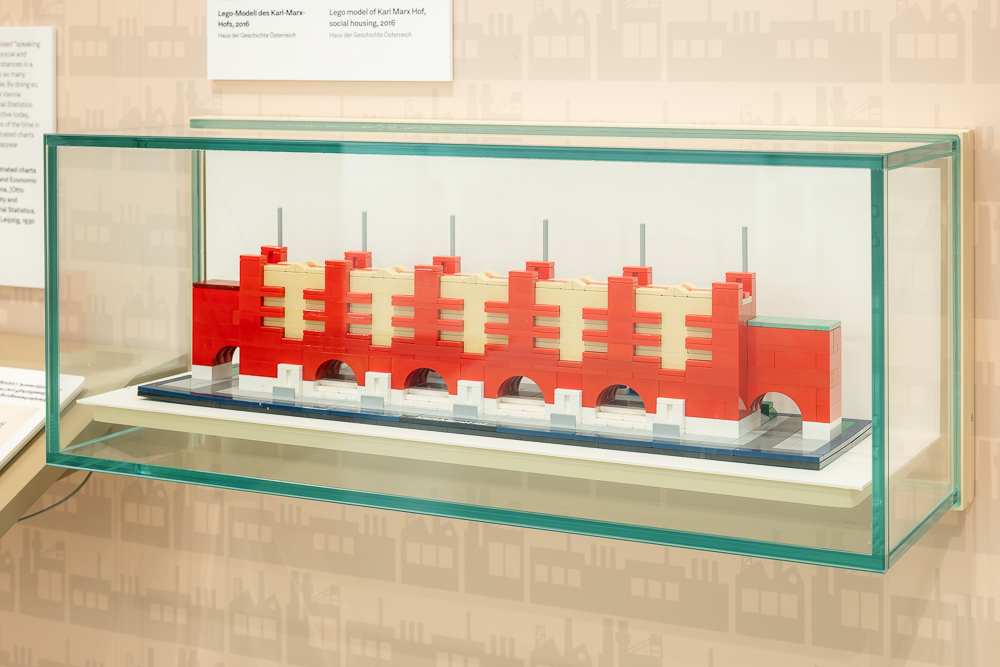

During this era, some cities—especially the Social Democratic “Red Vienna”—began to construct social housing. Luxury Tax was charged and then used to provide humane and affordable housing for the working class. This is a Lego model of “Karl Marx Hof”. It is one of the most famous social housing complexes in Austria.

In the 1930s, the international economic crisis resulted again in a catastrophic situation. Countless workers lost their jobs or had their wages cut. There were cutbacks on social welfare benefits. More and more people lived in poverty. In 1932, approximately 22 per cent of all Austrian citizens were unemployed.

During this time, the state only provided welfare to those who lived in the place they were registered in and for which they held a “Place of Origin Certificate”. This regulation dated back to the Monarchy and remained in effect until 1938.

This prevented people who had moved away from their “place of origin” from receiving financial aid from the municipality they later lived in. In the 1930s, this regulation affected around half of the people living in cities in Austria.

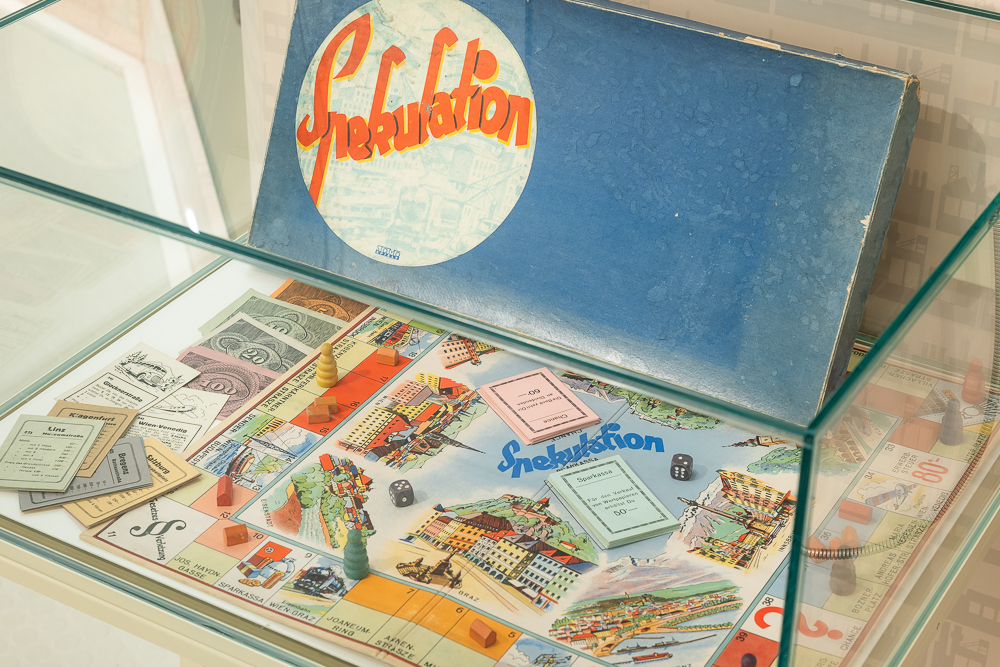

When you walk to the right, past the wooden clothes wringer and the display case with the board game “Speculation”, you will see another display case. Inside is a “Poverty relief fund cash book” of a small town that was deep in debt, because it was obliged to provide financial aid for many who had returned from the cities unemployed. Above it in a frame is a “Place of Origin Certificate”, a so-called “Heimatschein”.