Hugo Meisl (1881–1937)

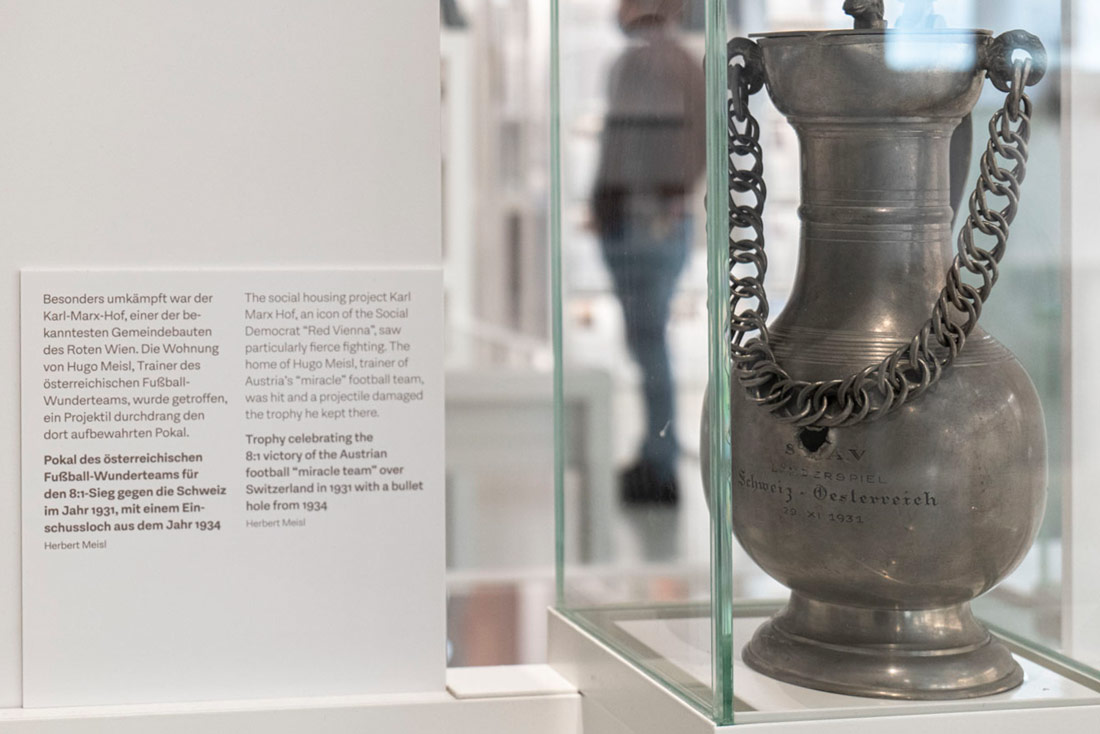

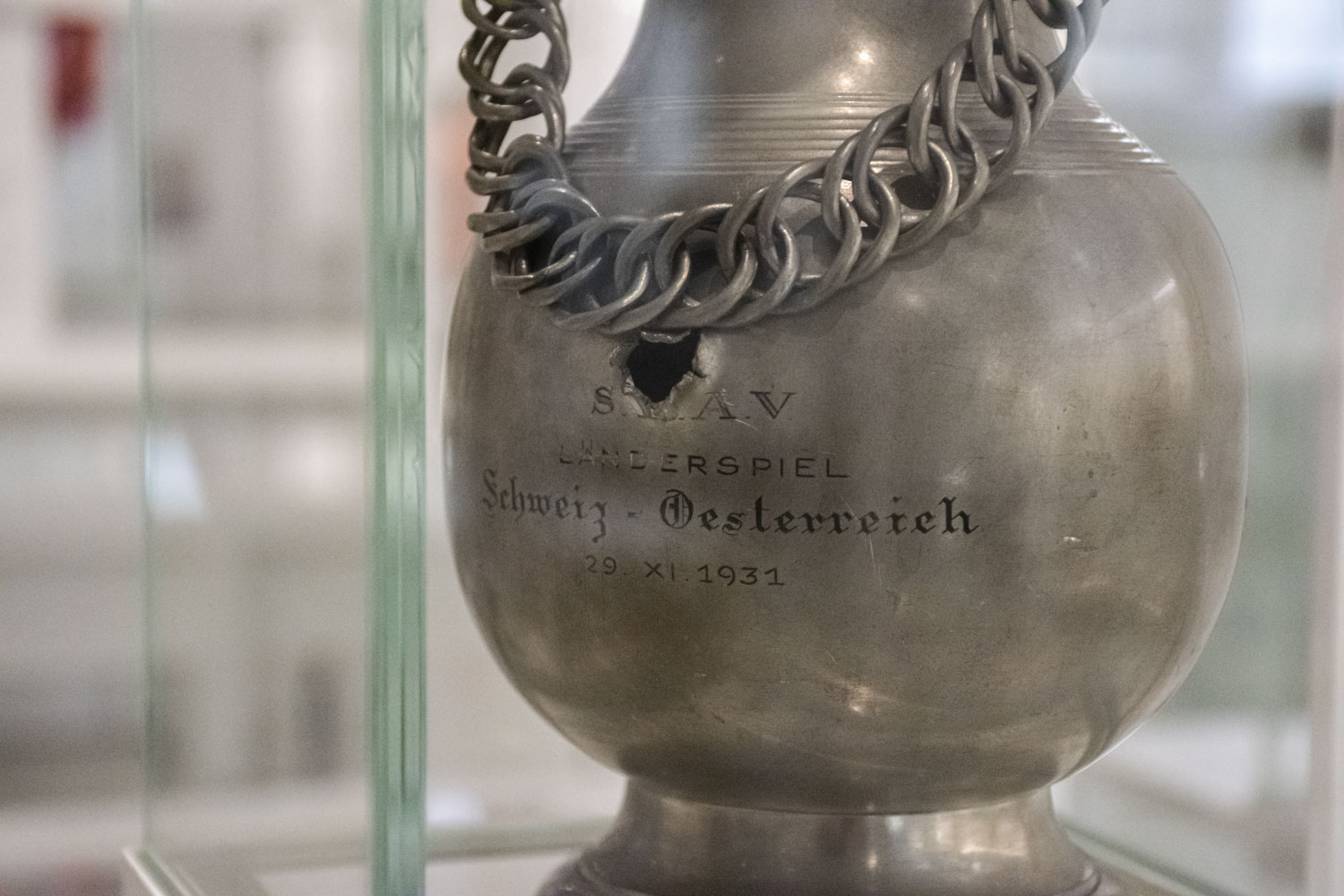

In front of you is a football trophy. If you take a close look, you see an engraving with the words “Schweiz – Österreich”, “Switzerland – Austria”. With a phenomenal score of 8 to 1, the Austrian national football team won this game in 1931. This was part of a winning streak that helped give the team its nickname: the “miracle team”. After beating Scotland 5 to 0 in 1931, the team went on to win 12 out of 16 games; rose to international fame; and took the European Championships.

This trophy was kept in the home of the team’s captain and trainer, Hugo Meisl.

At an early age, Hugo Meisl already had a passion for the new sport of football. As a referee, sport journalist, officiator and trainer he contributed a great deal towards professionalizing the sport of football—and to an entirely new style of playing also known as “Scheiberln”.

Meisl was well-known for his often blunt and direct statements, for his walking stick and bowler hat, and for his astonishing ability to speak many languages, which helped him to build international networks for the sport.

The trophy doesn’t just conjure up memories of Hugo Meisl and the “miracle team”, it also tells another, completely different, story. You may have noticed the hole in the trophy.

It was pierced by a gunshot during the Battles of February in 1934—making this trophy a special kind of witness to the contradictory developments of the early 1930s: while the “miracle team’s” international success paved the way for a new Austrian patriotism; at the same time, Austrian society was becoming more and more divided and radical.

The trophy was kept in the Meisl family apartment in the Karl Marx Hof social housing complex in Vienna. Karl Marx Hof was one of the main stages of the Battles of February in 1934.

In 1933, Chancellor Dollfuss began to dismantle democracy step by step. In February 1934, armed units of the Social Democrats took up weapons in an attempt to resist the government. The uprisings only occurred in a few places in Austria; and the Federal Armed Forces and the “Heimwehr” quickly put an end to them.

During the uprising several apartments at Karl Marx Hof were destroyed, including Meisl’s. The display table in front of you includes further items and documents around this event, such as photographs of Karl Marx Hof after the fighting.

Hugo Meisl’s choice to live at Karl Marx Hof shows that he leaned toward the Social Democrats. That said, football was far more important to him than politics.

Meisl passed away in 1937; and his funeral was a major social event. Extensive obituaries appeared in newspapers throughout Europe—only the press in Nazi Germany remained silent: Meisl’s family was Jewish. Long after 1945 the impression Hugo Meisl left on the sport remained in the shadows—only in recent years has the “founding father of modern football” been recognized.