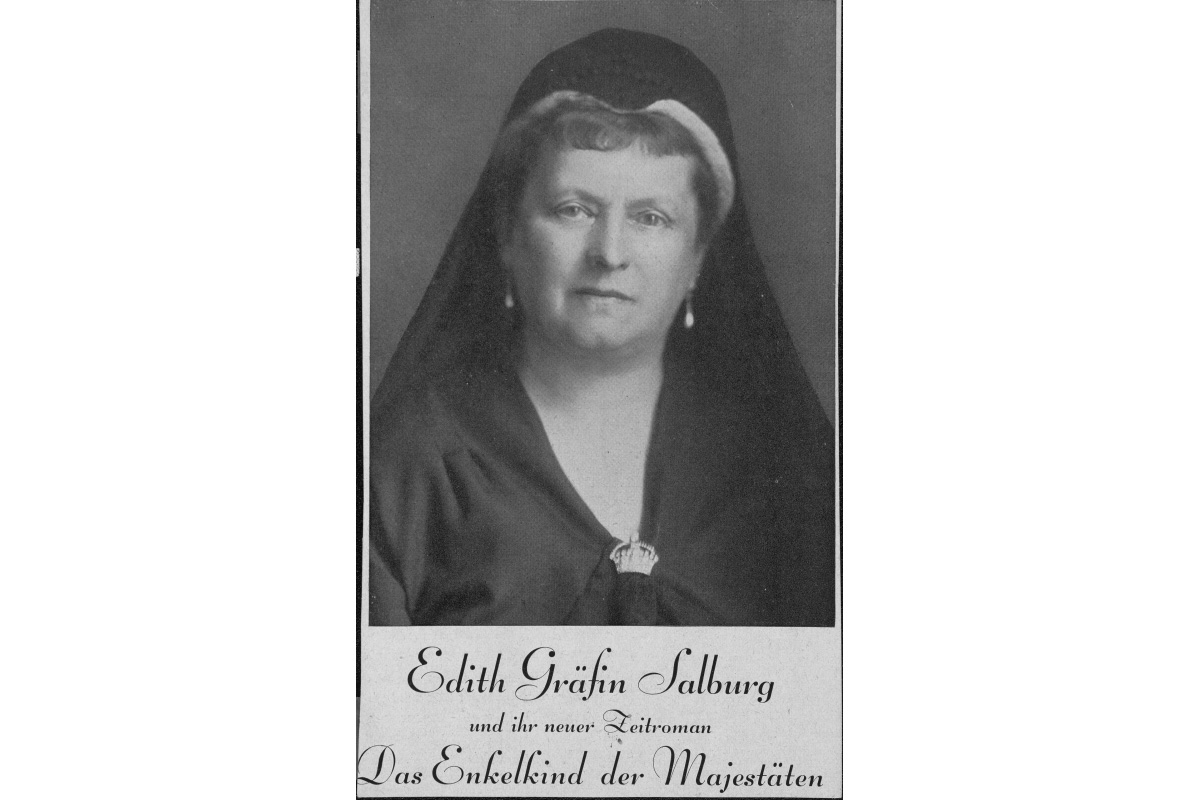

Edith Salburg (1868–1942)

You are now standing in front of a portrait of author Edith Salburg. In this exhibition, her story is an example of how the new borders affected individuals’ lives.

Edith Salburg was around the same age as Adelheid Popp. She too had taken a political stand under the Monarchy—although quite a different one.

In 1868 Salburg was born into a family of nobility. She grew up in Graz where she also attended secondary school. She acquired many of her ideas and interests from the German nationalists who played a key role in the social and cultural life in the city.

She later moved with her husband to Trentino, which is Italy today, but at the time was still part of the Habsburg Monarchy. For most of the First World War she remained in Switzerland.

She began writing at a young age. In her work, she addressed social issues in a critical manner. Although a noblewoman, she was critical of the Monarchy and nobility. As a German nationalist, she believed all German-speaking people belonged to one “German nation” that was superior to all other “peoples and nations”. She also believed all German-speaking people should be unified in one state.

The Republic founded in Vienna in 1918 was called German Austria. The name reflected the intention to form a state with the German Republic. It seemed that Salburg’s wish had come true. However, the treaty laid out by countries that won the First World War specifically prohibited Austria from joining Germany.

At that time, married women were given their husband’s citizenship. Edith Salburg’s husband was born in what later was known as Czechoslovakia. So in 1921 Edith Salburg, an Austrian German nationalist, became Czechoslovakian. In her autobiography from 1928, she calls herself “stateless”. She writes “I am all alone in this world. Separated from this fatherland of yesteryear that is now on its deathbed. And so I dedicate my life to the aim of my German Austrian fatherland coming together as one with the German Reich.” End quote.

After the First World War she moved to Bavaria, then to Dresden. From the 1920s onwards she openly showed her affinity to Nazi ideology, also in her novels.

Salburg died in 1942. After the Second World War, her books were banned in Austria.