Forced Labour and the Kaprun Power Station: The Subjugation of Humans and Nature

When the Second World War began in 1939, the Nazi state also began to force people to work: prisoners of war and civilians they had abducted from occupied territories.

In the summer of 1944 alone, outside of the concentration camps, the number of forced labourers across Europe was 14 million. In what is Austria today, there were around 550,000. The actual circumstances of forced labourers—and their chances of survival—depended on what supposed “race” the Nazis attributed to them. Soviet prisoners of war were subjected to the most inhumane working conditions of all.

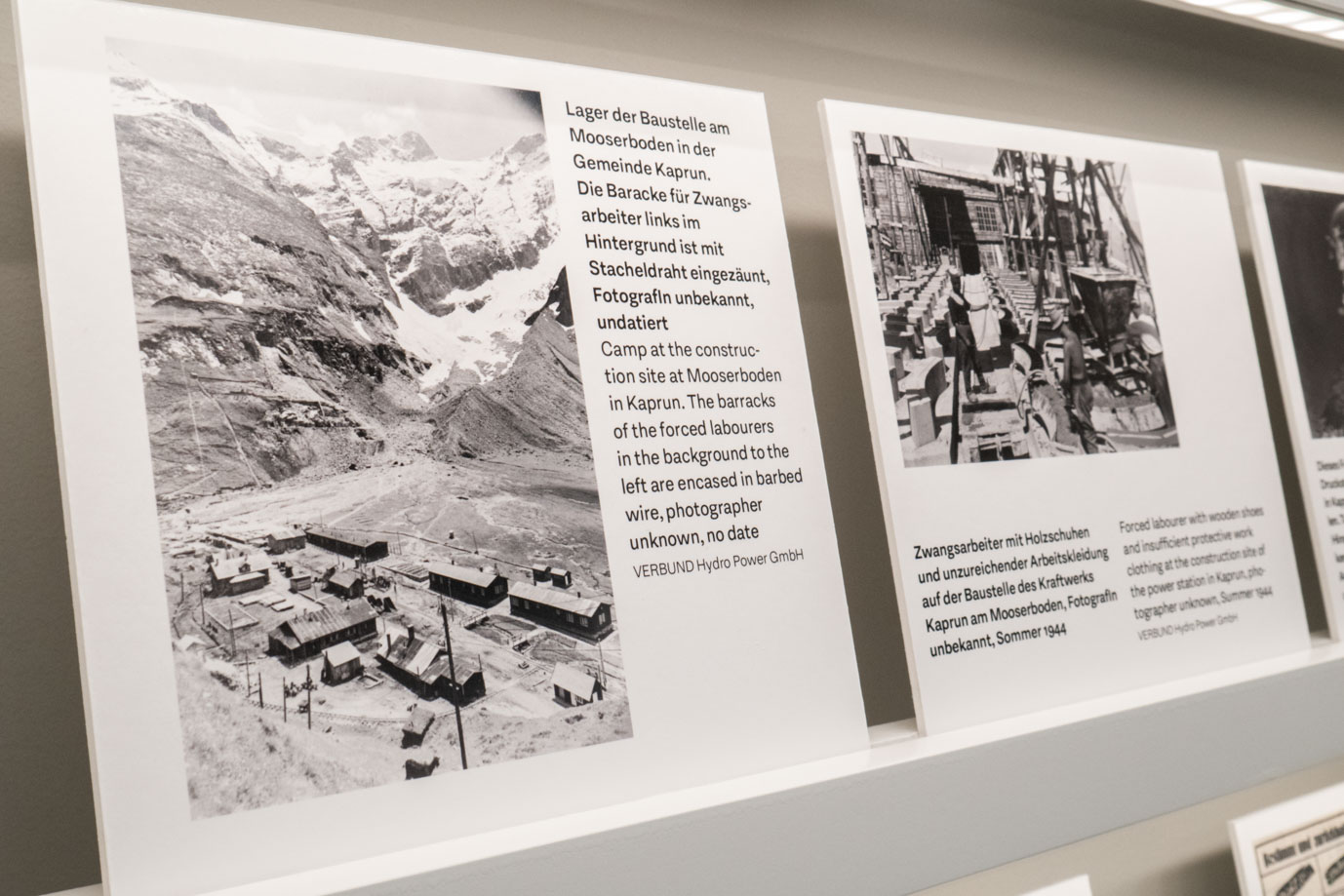

The photographs in the second row from the top are from a rural area in the province of Salzburg called Kaprun in the Hohe Tauern Mountains. Around 10,000 forced labourers worked on constructing the power station there between 1939 and 1945. One photograph shows men at work wearing simple wooden shoes. Another photo shows a row of barracks, the one in the very back is fenced in with barbed wire.

Under the Nazis, exploitation of humans and nature went hand in hand. In May 1938, shortly after the so-called “Anschluss” when Austria joined the German Reich, Hermann Göring, then Minister of Trade and Industry, ceremoniously opened the power plant’s building site in Kaprun.

This project combined romantic and technocratic ideas, which went hand in hand with the Nazi’s idea of nature conservation. This is evident in Hermann Göring’s speech at the site in Kaprun: “The wonder of nature is united with the wonder of technology.” End quote.

This “union of wonders” consisted of building several water reservoirs. The Kaprun power station was supposed to provide electricity to wide areas of what the Nazis called the Ostmark, that is, Austria today.

By the mid-19th century, large-scale projects that sought to tame and alter waterways were happening all around the globe. Since 1900, an increasing number of dams have been built to prevent floods, reclaim land and especially to generate energy. Power plants were not only economically important, but they were often also politically and symbolically meaningful.

Plans for the power plant in Kaprun had already been drawn up in the First Republic and during the Dollfuss-Schuschnigg dictatorship. It was finally completed in 1953 and consists of four water reservoirs; the highest is at around 2,000 meters above sea level.

Most of the construction work on the power plant was only completed after the war ended, and through the financial support of the US and others. But the fact that it began as a prestigious project for the Nazi regime was not spoken about for a long time.

Instead, the Kaprun Power Plant became emblematic for the reconstruction era after the Second World War, and for the economic advancements of the young Second Republic of Austria. The “Myth of Kaprun” symbolized not only the country’s ability to provide energy and thus ensure prosperity, but also the ability to conquer and tame the “wild” nature.