Consumption and Crisis: On Growth and Its Limits

“The great upswing began for us in 1948! The first thing we got was a 125 Puch moped. We loved it so much that we even put it by our bed so we could look at it until we fell asleep. My husband’s next greatest wish was a car. But before that we also wanted a child.”

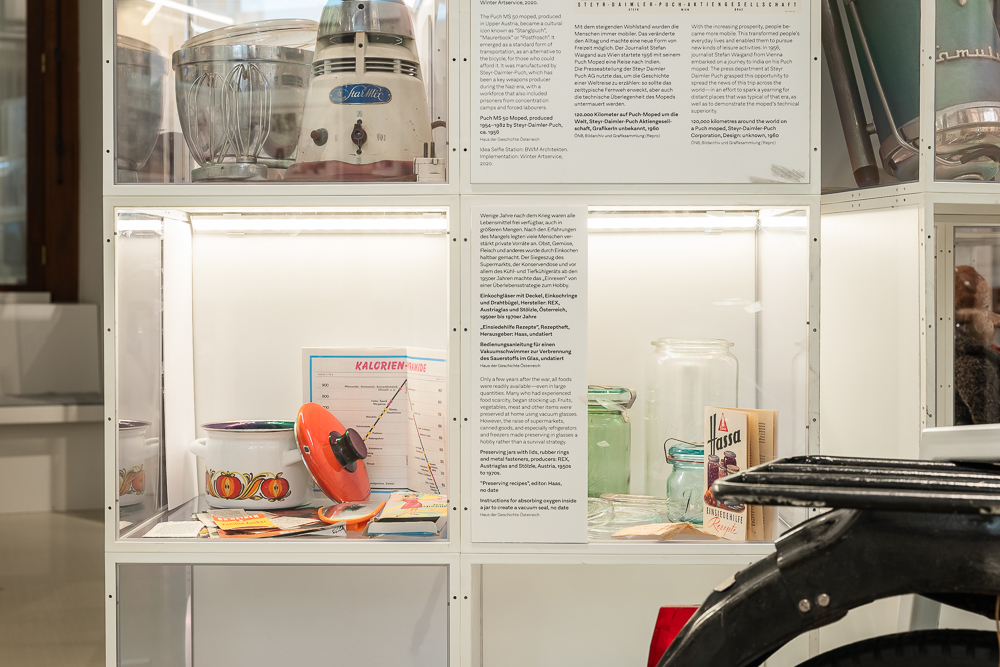

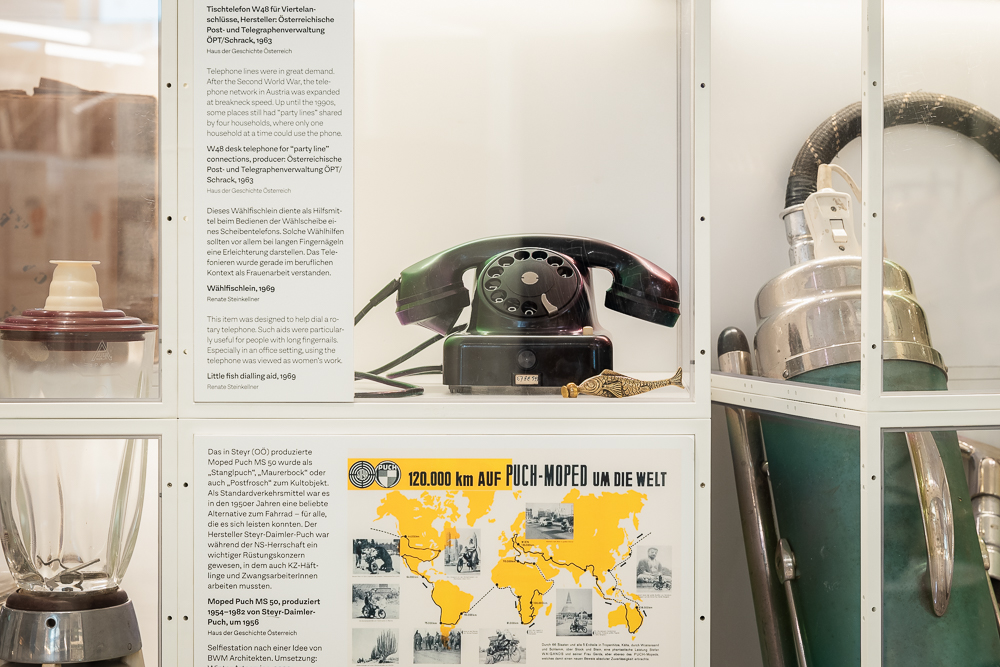

That is how Wilhelmine Hinner recalls the time after the war. A Puch Model MS-50 moped is also included in this exhibition. Behind it, you see a number of household appliances of the same era.

The hard times people had experienced during the Second World War and in the years immediately afterward were followed by a strong economic upturn in Austria. People’s disposable income increased, while mass production made consumer goods more affordable.

Signs of the economic upturn and the modernization of society included the purchase of new “American style” kitchens with refrigerators, the introduction of household washing machines, vacuum cleaners and individual vehicles for transportation—bicycles, motorcycles and cars—which for many was the height of all material possessions. As mobility grew, so did the desire to go on holiday. Cars allowed families to go on their first holidays—even to the seaside.

For a very long time, nobody questioned society’s orientation toward progress and growth. In the late 1960s, however, across the globe, the environmental impact of mass consumerism and increased mobility began to show more clearly.

In 1972, the non-profit organization Club of Rome published a report called “The Limits to Growth”. It demonstrated in simple terms the urgency for an international environmental policy. Around that same time, the first environmental protection organizations were founded, some of which are still active today, the best known are Greenpeace and WWF.

In 1973, political developments in the Middle East led to the first “oil price crisis”. Until then, large quantities of petroleum had always been affordable and readily available. This clearly showed how much the industrialized countries were dependent on petroleum and on global political developments. The euphoric belief in unbroken progress was dampened.

Austria’s response to the crisis included calling for “car-free days”: car owners had to determine one day of the week when they would not drive their car. So-called “Energy holidays”, one-week long school holidays in February, were introduced in Austria to save energy in schools and public offices during the coldest time of the year. These holidays still exist today, but have been renamed “Semester Break”. Due to the oil price crisis, efforts were feverishly made to access a new kind of energy—atomic energy—, which you will hear more about at the following station.

Consumer society also quickly became a throwaway society—resulting in enormous amounts of trash. The first waste burning facility in Austria opened in 1964. Over the years, awareness around waste disposal and recycling has increased. Yet, at the same time, the amount of materials and energy consumed in countries like Austria has also rapidly increased.

Today, we are still very far from establishing a true effective circular economy—that considers the re-usability of a product from its design to its production process.