Idealized and Tamed: Images of a New Austria

The Grossglockner High Alpine Road opened in 1935. It traverses mountain passes at over 2,500 meters above sea level, making it Austria’s highest mountain pass road for cars.

This high alpine road was not only built to connect two valleys. There were also economic and political interests at stake: the government under the Dollfuss-Schuschnigg dictatorship sought to demonstrate that it was capable of creating jobs.

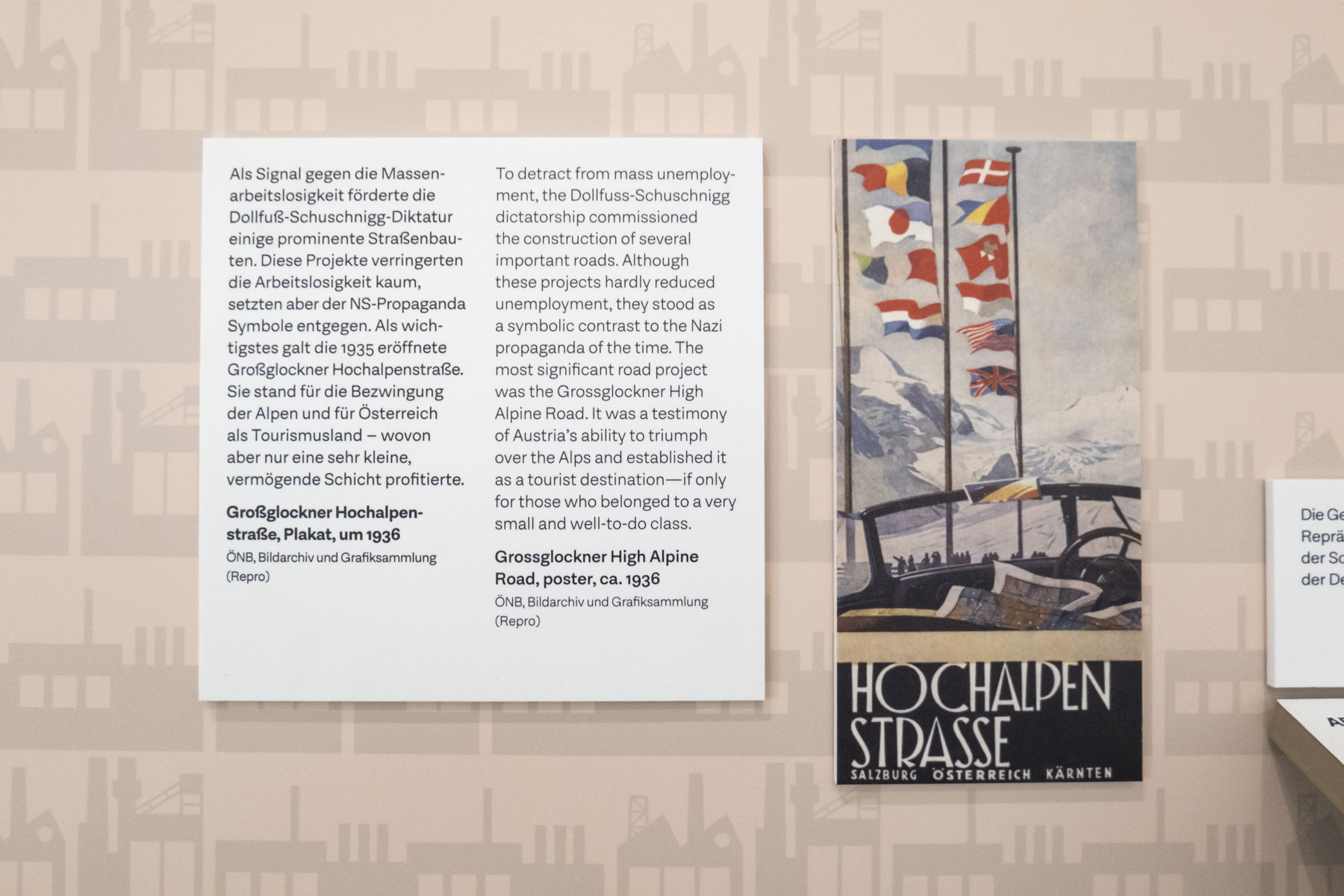

At the same time, the road was also supposed to attract tourists. The campaign poster with lots of flags on it refers to promoting Austria as an Alpine country and tourist destination.

Thus, the construction of this road also had great symbolic meaning. It was celebrated as an exceptional accomplishment and deemed a symbol of national pride. In 1935, the General Automobile Magazine wrote, quote:

“Grand and spectacular, the Grossglockner high alpine road is the work of a decade and takes you across the magnificent stone massif of the Hohen Tauern mountains […] The construction of this new road is a testimony to Austria’s strong will to live and its vitality.”

End quote.

In that same magazine, the governor of Salzburg describes the construction process as, quote, “waging a war of technology against virtually impenetrable mountain massifs.”

Later on in this audio guide you will hear more about how such colossal building projects often serve economic, pragmatic as well as symbolic interests, such as a display of state power and skill. In such cases, nature is portrayed as an “untamed” opponent that humans must conquer using technology and rationality.

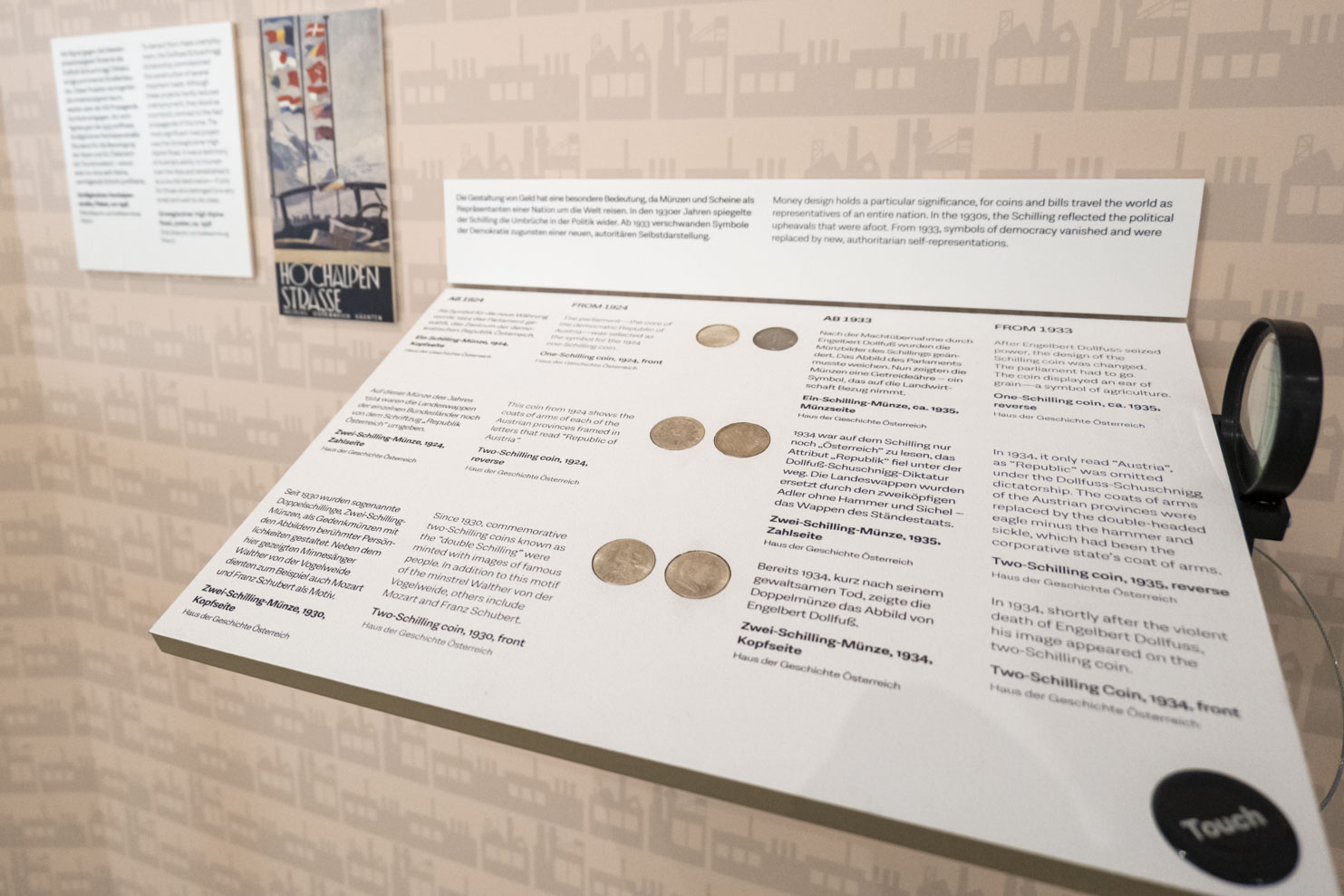

Banknotes and coins offer another opportunity for the state to select symbols that convey a certain self-image. The six coins to the right of the poster show the political rupture in 1933/34. In 1933, Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss’s government began to refashion the democratic republic founded only in 1918 as a dictatorship.

The Schilling coin in the left upper corner depicts the Parliament as the heart of democracy. In 1934, the Schilling coin was changed. The coin on the right has an ear of wheat. It’s not easy to see exactly what is printed on the coin, so we have provided a magnifying glass if you'd like to take a closer look.

The ear of wheat stands for agriculture. During the Dollfuss-Schuschnigg dictatorship agriculture played a pivotal role, both economically and ideologically.

The dictatorship sought to replace the democratic republic of Austria with a so-called “Ständestaat”, a “corporate state” that divided society into professions, such as agriculture, industry, or public office. According to the state ideology, people “naturally” took on a certain profession they were meant to have.

Farm work and the agricultural “profession” were romanticized and glorified and, figuratively speaking, farmers were idolized. Doing the hard work to create “daily bread” from nature itself also had religious undertones—of doing “God’s deed”. Idealizing life on the farm was part of the cult around Dollfuss as a leader, who himself came from a family of farmers. A publication dedicated to the life and work of Dollfuss was called The Heroic Chancellor. A Song from Native Soil. The "native soil" referred to here was the land a farmer inherited and rendered fertile through his labour.

When the so-called “Anschluss” took place in March 1938, the Dollfuss-Schuschnigg dictatorship was replaced by the Nazi regime. The Nazi ideology also frequently referred to “native soil”, yet in a clearly more militant and racist manner.