Repressing Memory and Remembering: Addressing Nazi Crimes in the Second Republic

In 1945, the allied forces liberated Austria from the Nazis. The Second World War was over, and Austria was once again a democratic state. This is why the time after 1945 is called the Second Republic.

But how were the Nazi crimes dealt with?

Here you see handwritten envelopes with letters that were sent to Austria from Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia between 2000 and 2005.

The address on all these envelopes is the Austrian Reconciliation Fund. Its purpose was to provide compensation for forced labourers. The Nazis had abducted people from all over Europe and forced them to work, for instance, in weapon factories or agriculture.

The forced labourers worked under largely inhumane conditions. In the summer of 1944 alone, over half a million people were subjected to forced labour in the territory which is Austria today.

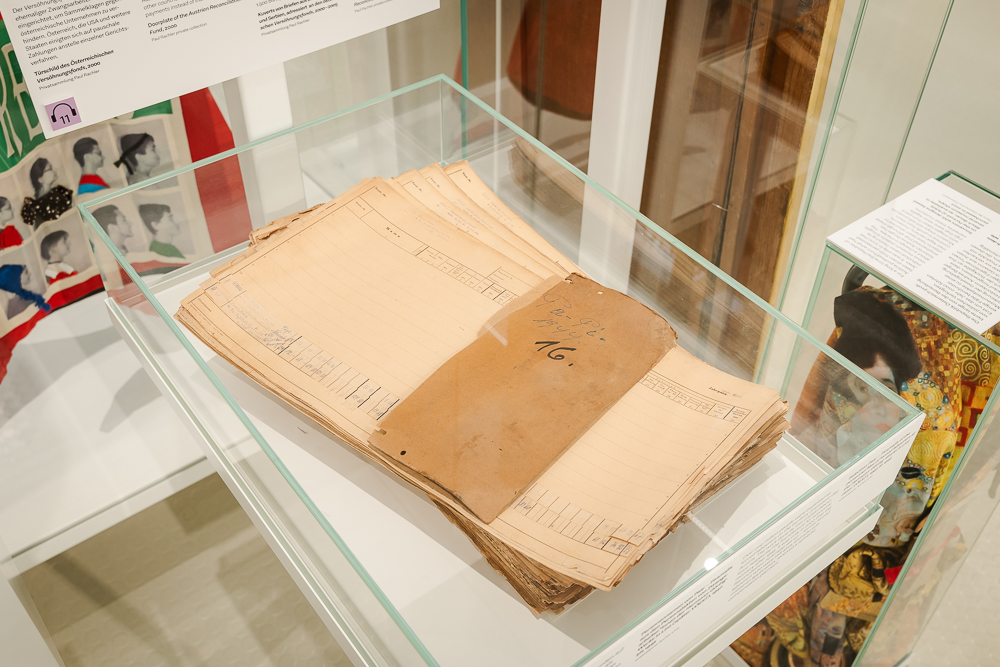

The stack of yellowed papers in the display case is from the former Hermann Göring Works in Linz, today called VÖEST. This is but a small sample from the personnel files of people forced to work there between 1940 and 1945. Each page represents one person. This huge pile of papers is only of the people whose last names begin with the letters Paa to Pi.

After 1945, there was a short intensive phase when people were tried in court for crimes committed under the Nazi regime. But quickly thereafter Austria changed its narrative, claiming the country had been the “first innocent victim” of the Nazis.

This drew the attention away from those who had really suffered under the Nazis, and for several years many fought for recognition and reparations. However only in the 1980s did this became a topic of broader public debate, and gradually different groups of victims were recognized.

The issue came into the spotlight particularly during the debates around the 1986 elections, when Kurt Waldheim became President.

The Reconciliation Fund that was supposed to provide compensation for forced labourers was established late. By the time it was founded, only about 15 per cent of the people who would have been entitled to compensation were still alive. The compensation consisted of a one-time payment of a symbolic amount of 1,500 to 7,500 Euros.

“Reparation” remains an important, although often unattainable goal. Working through past injustices inflicted upon people within a country is however a foundational—and not merely a symbolic—pillar of a democratic society. The way of dealing with Austria’s Nazi past was—and still remains—a matter of key importance for the Second Republic.